Unbroken

Embracing who you are and what you need

|

What’s up with our personalities and behaviours? Many of us have a diagnosis that has something to do with the way our mind works—and if not, we probably know someone who does. It’s hard to hang out in the 21st century without encountering people who have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), bipolar disorder, anxiety disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), depression, autism spectrum disorder, and other neuropsychological diagnoses.

These diagnoses can help us understand ourselves and figure out what makes it easier for us to thrive. This might involve environmental supports (e.g., a quiet classroom), behavioural approaches (e.g., a mindfulness routine), some kind of therapy or life coaching, friends and partners who get it, or medication.

For some, though, the prospect of a diagnosis is problematic. A diagnosis may seem judgmental, stigmatizing, or overly simplistic. We may ask ourselves:

- Does this mean I’m not “normal”? Can I be happy with myself as I am? Does this label me?

- What should I do with my diagnosis?

- How can it help me?

What’s “normal” & does it matter?

When does a personality trait or behaviour become a diagnosis? Is our understanding of “normal” too narrow? “People are wired differently and have different needs, yet we’re expected to behave in a similar fashion,” says Julius V., an undergraduate student at the University of Victoria, British Columbia. What we’re talking about is medicalization, “the idea that we’re turning all human difference into a disease, a disorder, a syndrome,” says Dr. Peter Conrad, Professor of Sociology at Brandeis University, Massachusetts, who specializes in “how conditions get to be called a disease and what the consequences are.”

In recent decades, the diagnostic criteria for many neuropsychological conditions have broadened. “More and more human behaviour has been defined as a disorder, especially around the edges,” says Dr. Conrad. “Human problems are increasingly medicalized, especially sadness. Eleven percent of the [US] population has ADHD, according to the CDC. At that rate, it’s something that’s fairly normal and not necessarily a pathology.” This does not mean medicalization is a bad thing; it has helped countless people access treatment and supports.

The pros & cons of medicalization

Like anything, medicalization has risks and benefits

The risks of medicalization include:

- Discomfort with the premise that there’s something wrong with us.

- “Medicalizing behavioural issues, like substance abuse, frames them primarily as individual problems as opposed to collective social problems,” says Dr. Peter Conrad, professor of sociology at Brandeis University, Massachusetts. This may deter us from tackling relevant societal factors, such as discrimination and poverty.

The benefits of medicalization include:

- Reducing the stigma attached to certain conditions.

- Conditions defined as illnesses can be covered by health insurance, improving access to treatment and accommodations.

- “It used to be thought that the devil had come to people with epilepsy, but with better medicines and reduced stigma, more people with epilepsy have been able to survive,” says Dr. Conrad.

Got neurodiversity?

Behavioural health and disability advocates are working to change the way that these conditions are understood. Their key point: Different kinds of minds come with different kinds of strengths (as well as challenges). Many unusual thinkers and innovators—people who may have been considered sick, disabled, or eccentric, have made critical leaps in the sciences, arts, and technology.

The concept of neurodiversity acknowledges and helps us accept these natural human differences. “Neurodiversity may be every bit as crucial for the human race as biodiversity is for life in general,” wrote journalist Harvey Blume, who introduced this idea to a mainstream audience in The Atlantic (1998); “Cybernetics and computer culture, for example, may favor a somewhat autistic cast of mind.” Neurodiversity is particularly associated with autism, but embraces all other neuropsychological disabilities too. (There is arguably no effective distinction between mental illness and neuropsychological disability; here, “disability” encompasses both.)

In the pro-neurodiversity model, the goal is to help us all thrive without judgment and negativity. “One way to understand neurodiversity is to remember that just because a PC is not running Windows doesn’t mean that it’s broken. Not all the features of atypical human operating systems are bugs,” wrote Steve Silberman in Wired magazine; his book NeuroTribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity will be published by Avery/Penguin in August.

How neurodiversity helps

Dr. Christina Nicolaidis, a professor at Portland State University and a physician, is committed to a pro-neurodioversity approach in her clinical practice and her academic research. She points to ways that this mindset supports us:

Valuing ourselves & accepting our needs

Neurodiversity does not mean denying our disability or condition. “A neurodiversity-based approach can be conducive to dealing with the dissonance between accepting yourself, understanding yourself, and being happy with who you are, while also acknowledging that you may need supports, accommodations, and medical treatments.”

Advocating for ourselves and others

“The neurodiversity movement sees people with disabilites as members of a minority group that have a right to be treated equitably.” Disability itself is not a minority issue. “The ‘universalist’ approach understands disability as a fluid concept that will affect every one at some point,” says Tess Sheldon, a lawyer with ARCH Disability Law Centre, Ontario.

Accessing health care & other supports

“In my clinical experience, a strengths-based and neurodiversity-type approach is extremely important for helping doctors understand, communicate with, and support their patients.”

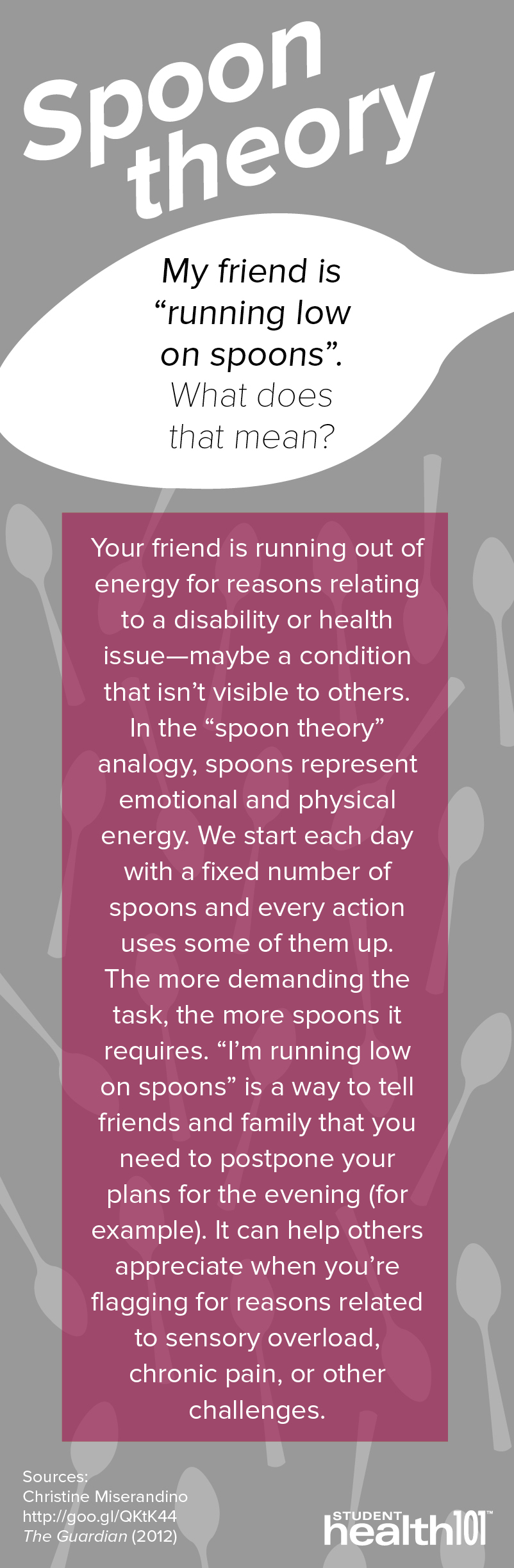

Spoon Theory

My friend is “running low on spoons”. What does that mean?

Your friend is running out of energy for reasons relating to a disability or health issue—maybe a condition that isn’t visible to others. In the “spoon theory” analogy, spoons represent emotional and physical energy. We start each day with a fixed number of spoons and every action uses some of them up. The more demanding the task, the more spoons it requires. “I’m running low on spoons” is a way to tell friends and family that you need to postpone your plans for the evening (for example). It can help others appreciate when you’re flagging for reasons related to sensory overload, chronic pain, or other challenges.

Sources: Christine Miserandino, http://goo.gl/QKtK44, The Guardian (2012)

A student’s story: “Diagnosis has the potential to greatly improve quality of life”

“I was diagnosed with ADHD in second year and started taking medication. The difference in my performance in school over the past two-and-a-half years is astounding. Treating this condition has also improved my health and day-to-day life.

“I think it is important for diagnoses to occur, as they have the potential to greatly improve the quality of life for those who are diagnosed.”

—Simon G.,* fourth-year undergraduate, Trent University, Ontario

*Name changed for privacy

How getting a diagnosis can help us

Access to medical and academic supports

“By having a legitimate diagnosis, students can qualify for accessibility accommodations, which can greatly help their academic success.”

—Jess G., second-year undergraduate, Mount Royal University, Alberta

Self-acceptance

“Proper treatment can ensue after getting proper diagnoses; knowing is half the battle.”

—Chris G., student in post-graduate certificate program, Fleming College, Ontario

Lifestyle adjustment

“Proper diagnosis of conditions enables one to change learning styles, life habits, etc., to make life easier, based on the condition. I am grateful for the commitment the health practitioners have to properly diagnosing these conditions. There are many stages of testing, and it is generally a long process for both the professional and the patient.”

—Ashley T., fifth-year undergraduate, University of Regina, Saskatchewan

Is it OK to say “I’m so depressed today”?

What’s the problem?

“It seems that ‘depression’ and ‘insomnia’ have become words to describe feelings or current moods rather than patterns of behaviour. Using these phrases takes away from the seriousness of mental health disorders and normalizes them. On one hand, using these terms allows people to talk about these issues and break the stigma around mental health disorders, but on the other, it may muddle the signs and symptoms of someone actually suffering.”

—Victoria P., fifth-year undergraduate, University of Waterloo, Ontario

On the other hand

When clinical terms move into mainstream casual use, it signals a broadening (if basic) awareness of neuropsychological difference.

Is modern life changing our brains?

“I think people get nervous about ‘over-diagnosis,’ but that isn’t necessarily looking at the full picture. If upbringing has changed in the last 20 years…it is reasonable to expect a new normal in mental health diagnosis.

“Nobody truly knows the effects of growing up in a home with [multiple screens, 24/7 internet,] external stimuli, and marketing reminding us of all the things we ‘need’ or ‘should want’ to keep up and be normal. Facebook shows us just how perfect everybody else’s lives are while managing to keep out most every negative aspect. There is increasing pressure to go to college and score well on tests [rather than] live with balance.

“The increasing diagnosing of neuropsychiatric conditions could be well within a normal response to our changing society. I am encouraged that there are people taking time out of their day to go seek help. That kind of behaviour, at a minimum, will help us prepare for the future.”

—Andrew C., fourth-year graduate student, Temple University School of Medicine, Pennsylvania

The concept of disability is created by society

Many of the challenges that come with disability are intrinsic to our society and culture, not to the disability itself. “Imagine a world where 99 percent of people were deaf,” wrote Dr. Christina Nicolaidis, a physician and a professor at Portland State University, in the AMA Journal of Ethics (2012). “That society would likely not have developed spoken language. With no reason for society to curtail loud sounds, a hearing person may be disabled by the constant barrage of loud, distracting, painful noises…The deaf majority might not even notice that the ability to hear could be a ‘strength’ or might just view it as a cool party trick or savant skill.” She notes that homosexuality was considered a psychiatric condition until 1973.

Is my diagnosis accurate?

What’s the problem?

“The DSM [the physicians’ guidebook to neuropsychological conditions] is not perfect (hence it is being revised on a regular basis), and a lot depends on the health professional’s own judgement.”

—Jennifer K., fourth-year undergraduate, Humber College, Ontario

“You can diagnose almost anybody with the DSM.”

—Tess Sheldon, lawyer with ARCH Disability Law Centre, Ontario

On the other hand

The way that neuropsychological conditions are diagnosed and categorized is evolving in line with the research. This is also true of many physical health conditions.

Scientists and physicians now understand that what can look like the same neuropsychological condition likely reflects varying causes and biological mechanisms; e.g., one person’s depression may involve different biological pathways than the next person’s. This is probably why people with the same diagnosis respond differently to medications, and why a range of treatment options is needed. Similarly, the same biological mechanisms may present differently in different people.

Consequently, research funding is shifting away from targeting diagnoses. Scientists are focusing instead on specific states of mind—such as anhedonia, a loss of pleasure—and specific biological processes.

Is it OK to diagnose myself?

What’s the problem?

“I think self diagnosis has become a bit of a problem. Saying that you are ‘anxious’ or ‘depressed’ is common, yet many people don’t know the actual feelings that come with those conditions.”

—Natasha W., fourth-year undergraduate, University of Guelph, Ontario

“Sometimes the individuals dianosing themselves might be on the edges of the diagnostic scale at either end. Individuals’ [behaviour] fluctuates day-to-day. Based on that, it’s easy to get a false reading on your own mental state.”

—Sarah G., fourth-year graduate student, University of Victoria, British Columbia

On the other hand

For those who are seeking self-identity, understanding, and community, self-diagnosis may have value. But you might need an official diagnosis for access to resources, services, treatment, and accommodations, many of which are important in a college or university environment. “Students may be allowed to take breaks to avoid overstimulation, have interpreters or facilitators to help with communication, be given advance notes or visual aids to assist in comprehension, have access to different living arrangements, counsellors, etc.,” says Alanna Whitney, an autistic artist, activist, and Chapter Leader of Autistic Self Advocacy Network in Vancouver, British Columbia. If you might need access to treatment or supports now or in the future, make an appointment with a qualified professional.

“Am I neurotypical?” Disability advocates diagnose “normality”

The term “neurotypical” arose in the disability community as a label for people who have typically-developing minds. Descriptions of “neurotypical syndrome” are satirical; they make the point that disability and “normality”can be a matter of perspective.

Neurotypical syndrome is a neurobiological disorder characterized by preoccupation with social concerns, delusions of superiority, and obsession with conformity.

Neurotypical individuals (NTs) often assume that their experience of the world is either the only one, or the only correct one. NTs find it difficult to be alone. NTs are often intolerant of seemingly minor differences in others. When in groups, NTs are socially and behaviuorally rigid and frequently insist upon the performance of dysfunctional, destructive, and even impossible rituals as a way of maintaining group identity. NTs find it difficult to communicate directly.

Neurotypical syndrome is believed to be genetic in origin. As many as 9,625 out of every 10,000 individuals may be neurotypical. There is no known cure for neurotypical syndrome.

Source: The Institute for the Study of the Neurologically Typical (parody)

Neurodivergent geniuses & celebrities

Diagnosing geniuses and celebrities, dead or alive, has become commonplace. In the absence of modern neuropsychological testing and openness on the part of the individual, such diagnoses are speculative—but in many cases the evidence is strong.

The super-scientists Albert Einstein (the theory of relativity) and Isaac Newton (the law of gravity) were probably autistic, according to a 2003 article in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine.

Thomas Jefferson, third president of the United States, likely had Asperger syndrome, according to Norm Ledgin, author of Diagnosing Jefferson: Evidence of a Condition That Guided His Beliefs, Behaviour, and Personal Associations (Future Horizons, 2000).

Richard Branson, businessman extraordinaire and founder of Virgin Group, has acknowledged in interviews that he has dyslexia and ADHD.

Sinead O’Connor has talked about her experience with bipolar disorder. Other candidates for this diagnosis include Kurt Cobain, Marilyn Monroe, Vincent Van Gogh, and Emily Dickinson.

Actor Leonardo DiCaprio, who has OCD, played Howard Hughes, who also has OCD, in The Aviator. “He let his own mild OCD get worse to play the part,” said the psychiatrist who advised him on set.